Bringing Out the Invisible, Making Time and Light Tangible

– Q3 ASIWEEK Winner Gianni Lacroce’s Astrophotography Journey Hi, I’m Gianni Lacroce, an Italian astrophotographer. My passion for the night sky began long before I owned a telescope or a

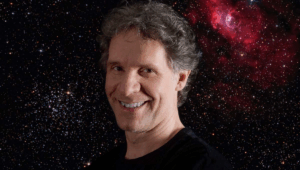

Author: Richard Harris

Author BIO:

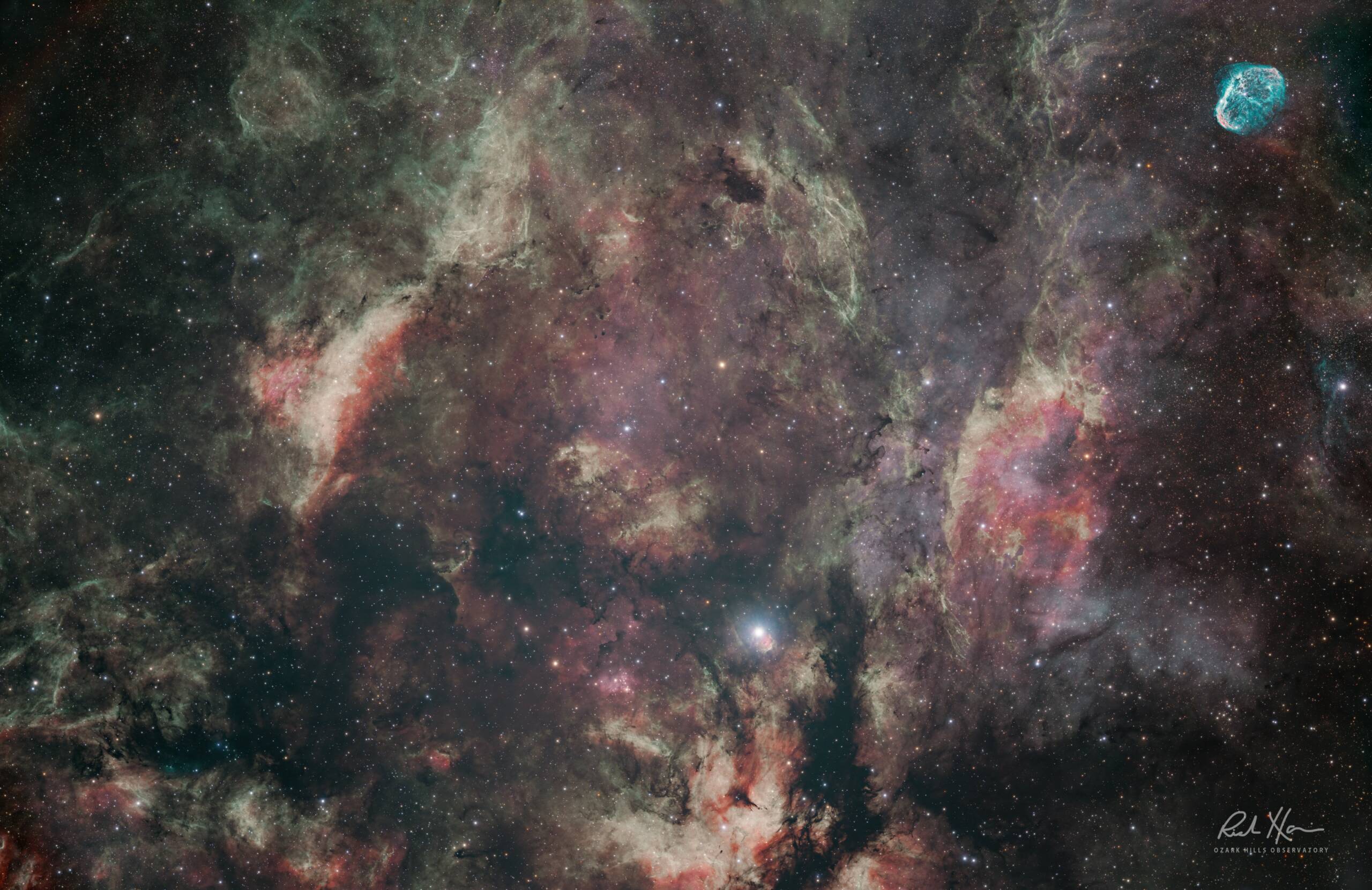

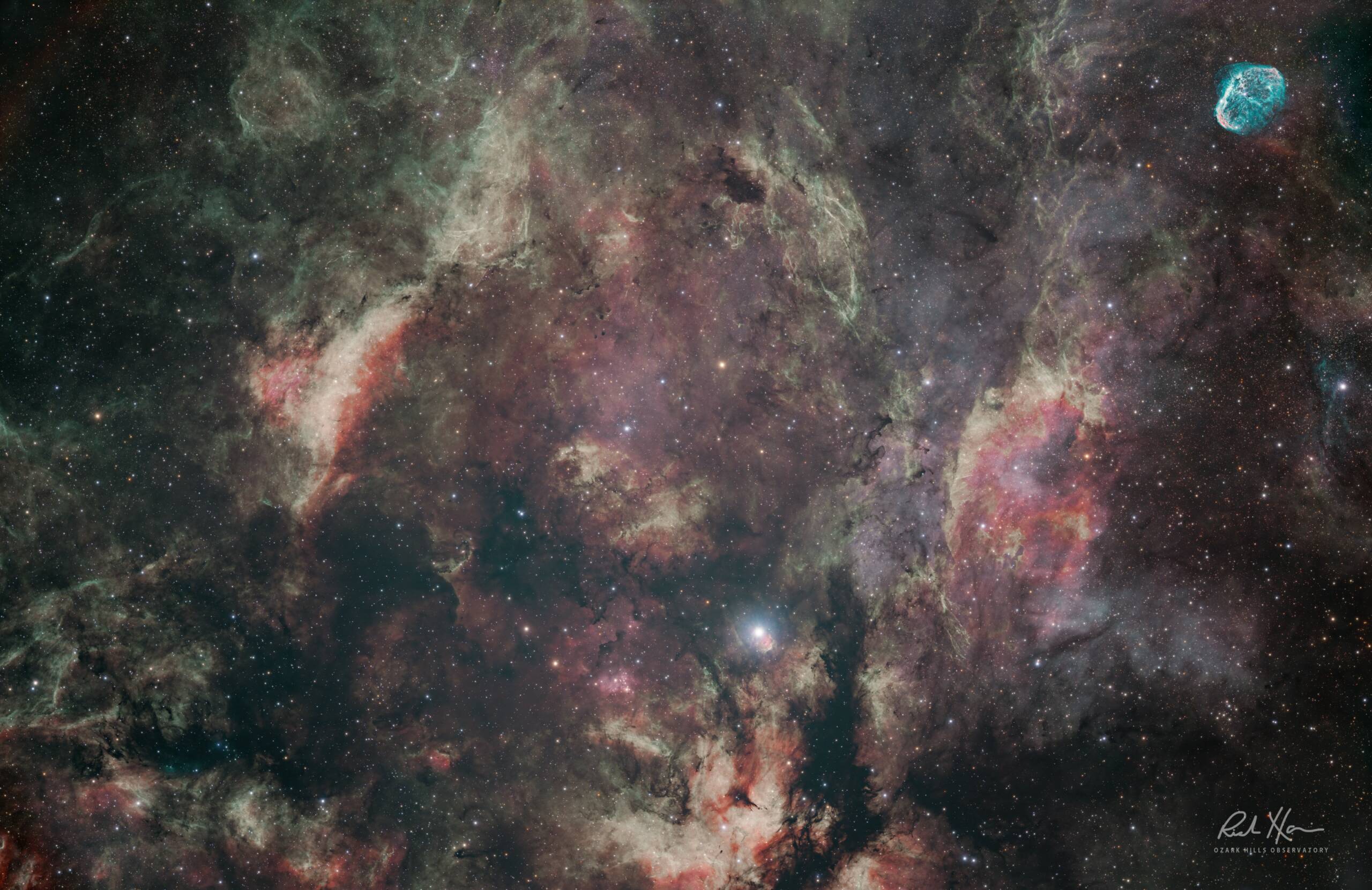

Meet Richard Harris. He is the founder and editor-in-chief of ScopeTrader, with over 30 years of experience in astronomy and astrophotography. He serves as the director of the Ozark Hills Observatory, where his research and imagery have been featured at NASA’s INTUITIVE Planetarium, scientific textbooks, academic publications, and educational media. Among his theoretical contributions is a cosmological proposition known as The Harris Paradox, which explores deep-field observational symmetry and time-invariant structures in cosmic evolution. A committed citizen scientist, Harris is actively involved with the Springfield Astronomical Society, the Amateur Astronomers Association, the Astronomical League, and the International Dark-Sky Association. He is a strong advocate for reducing light pollution and enhancing public understanding of the cosmos. In 2001, Harris developed the German Equatorial HyperTune – a precision mechanical enhancement for equatorial telescope mounts that has since become a global standard among amateur and professional astronomers seeking improved tracking and imaging performance. Driven by both scientific curiosity and creative innovation, Harris continues to blend the frontiers of astronomy and technology, inspiring others to explore the universe and rethink the possibilities within it. When he’s not taking photos of our universe, you can find him with family, playing guitar, or traveling.

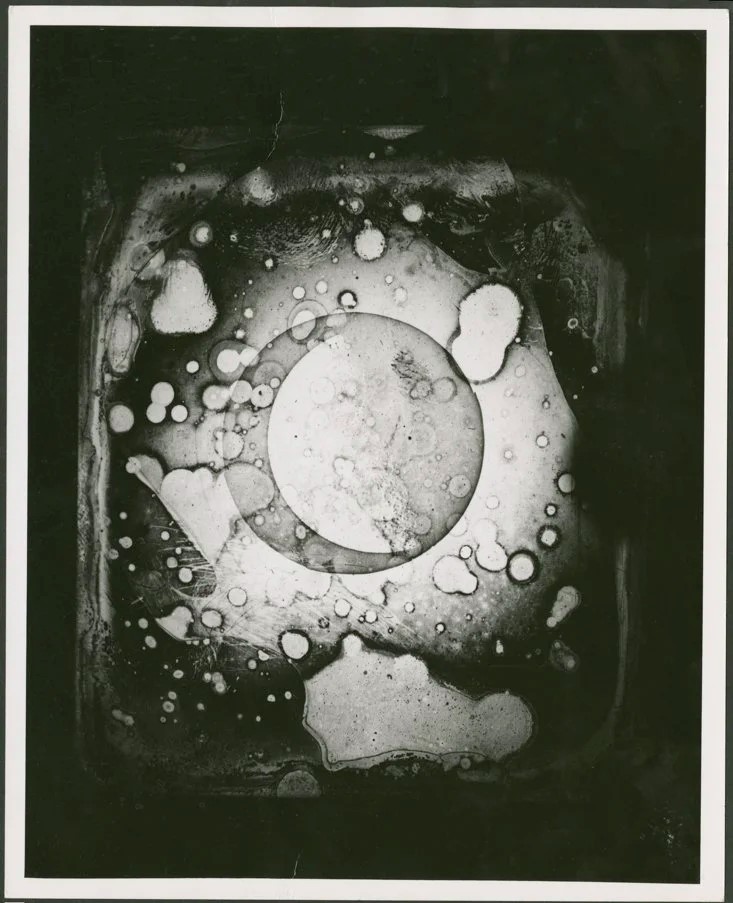

The very first “successful” astrophoto was a daguerreotype of the Moon, captured by an American (English-born) scientist John William Draper on March 23, 1840. Using a homemade 5-inch reflecting telescope and a twenty-minute exposure, Draper managed to imprint the Moon’s image onto a silvered copper plate. It marked the dawn of celestial photography. That moment, for Mr. Draper, must have been very emotional. Here was a man who had spent years mastering portrait photography, now turning his camera toward the heavens and succeeding where others had only dreamed. Others had attempted to photograph the Moon before him, but he was the first to produce a truly successful image. I can imagine Draper peering at the faint lunar likeness on his plate (the first time humanity had literally “captured” the face of another world) and feeling a profound mix of triumph and wonder.

“Every movement in the skies or upon the earth proclaims to us that the universe is under government,” he would say years later. Coming from someone who was among the first to capture the cosmos on film, it speaks volumes about how deeply the experience of astrophotography had shaped him. Photographing objects in space hadn’t just changed what he saw – it changed how he understood everything.

Astrophotography has been entwined with human emotion from the very start. Even decades later, scientific milestones in space often carried a spiritual or reflective undercurrent. When Apollo 11 landed on the Moon in 1969, astronaut Buzz Aldrin felt the moment transcended mere engineering; he quietly took communion on the lunar surface, making the first food and drink consumed on another world a sacrament. A year before that, the Apollo 8 crew, first to orbit the Moon, marked Christmas Eve by reading from the Book of Genesis while gazing at the Earth rising over the lunar horizon. These moments of looking back at our tiny blue planet or standing on the Moon’s barren plains were scientific achievements, yes, but they were also imbued with reverence. It’s as if whenever we reach farther into the cosmos, we can’t help but also reach deeper into ourselves.

For as long as humans have existed, we’ve gazed at the sky and tried to record its beauty. If you’ve ever snapped a photo of a glowing sunset or a full moon rising, you’ve practiced a bit of astrophotography – without even knowing it eh? Long before cameras, people painted stars on cave walls and built monuments like Stonehenge to track the heavens. This impulse to record the sky is deeply ingrained in us.

Even if you don’t think of yourself as an astrophotographer, that urge to capture the sky is in all of us. A child scribbling a starry night or a tourist snapping a quick photo of the Moon, both are trying to save a piece of the sky. Maybe we do it because looking up reminds us how vast the universe is, and how special it is to witness it. We want to hold on to that feeling and perhaps share it. In that way, astrophotography is part of everyone’s story, whether we realize it or not.

In the daytime, we live under a blue sky ruled by a single star. There’s only so much you can photograph in daylight beyond the Sun, clouds, and maybe a comet or a high-flying airplane. But when the sky darkens and night arrives, an entire universe of possible subjects emerges. The stars come out by the thousands; planets sparkle; the Milky Way stretches across the sky like a cosmic tapestry. Unlike during daylight, the night sky is deep and full of treasures waiting to be captured. With long exposures and sensitive cameras, we can reveal colors and details our eyes can’t see on their own.

Today, with an evolving buffet of telescopes, cameras, and gadgets at our disposal, we can see deeper and more clearly than ever. A hobbyist with a modest backyard setup can photograph distant galaxies millions of light-years away, or nebulae where new stars are said to be being born. Each advance in technology (better mounts, more sensitive sensors, smarter trackers) opens up new frontiers. It’s amazing when you think about it: not long ago, capturing a decent photo of Saturn’s rings or the Andromeda Galaxy required professional observatories. Now, determined amateurs do it regularly. Every clear night brings a rich menu of targets: the Moon, the planets, glowing nebulae, far-off galaxies. It’s easy to get carried away acquiring telescopes, lenses, mounts, guiders, filters, and more: all the gear to help us record what we see. Many of us lovingly joke that astrophotography is half art, half science, and half buying stuff you didn’t know you needed. We spend long nights under the stars gathering ancient starlight onto our sensors, all to preserve a moment of the cosmos in an image.

But this all begs the question: why? Why do we do this, really?

It’s a question that every astrophotographer gets asked eventually, whether by a friend or by their own tired reflection during a 3 AM imaging session: “Why do you do this?” Why spend hours (sometimes entire nights) in the cold darkness, fighting sleep and often fighting equipment, just to collect photons from a faint smudge in the sky? Why devote days to processing a photo of a galaxy that, to the uninitiated, looks like just another pretty picture you could download from the internet? On the surface, there are plenty of answers, and I’ve given them myself over the years. I might say, “I love space,” or “I’m an astronomy nerd,” or “I enjoy the challenge and the gear.” Those answers are true, as far as they go. Many of us are drawn in by a love of astronomy or by the cool technology. There’s certainly a thrill to using precision instruments to capture light that’s traveled across the universe.

Yet those answers feel a bit superficial, don’t they? They don’t fully capture the heart of it. If you really stop and soul-search, digging into the core of why you shoot astrophotography, you’ll discover something more meaningful beneath the surface. It took me decades to articulate my own reason. But I think I can sum it up now, and I suspect many fellow stargazers have similarly deep currents running under their hobby, even if they describe them differently.

“For me, astrophotography is fundamentally a way to connect with creation (both the physical universe and something beyond the physical).

As delicate as a dandelion drifting on a warm summer breeze, and as fierce as the storms of spring, Earth holds such a balance that’s both fragile and powerful. Looking out at the universe from our tiny corner of it reminds me just how rare life truly is. Our planet hosts an estimated 8.7 million eukaryotic species – animals, plants, fungi, and more – yet despite all our searching, we’ve found nothing like it anywhere else. Not even close.

I have a passion for pushing technology to its limits, but I also have a deeply rooted faith. In my case, pointing a camera at the sky is a form of worship as much as it is a scientific pursuit. Every time I capture a distant nebula or galaxy, I feel like I’m memorializing that encounter, making it a permanent part of my journey as a human on planet Earth. Each image I produce isn’t just a picture; it’s a page in my own little cosmic scrapbook, a personal memento of a moment when I reached out across the void and touched a piece of the heavens.

I often feel like a tiny speck looking up at a giant, and daring to say “hello” and document that meeting. There’s reverence in it, a nod to the Creator (in my view) or at least to the majesty of nature. And there’s also a deep personal satisfaction in having used my skills and tools to forge that connection.

That photograph is mine. I made it. It was my way of saying hello, my way of standing on the summit. Even if no one else ever sees it, the light that filled those pixels came from a quiet dance between my soul and the universe. The gear just helped me reach the edge of that conversation.

I’m a witness to it. And being a witness to something so incredible, changes you.

For example, you can tell someone how beautiful Alaska is, but words do almost nothing. You can’t explain what the air smells like, how the cold feels sharp and clean in your lungs, how impossibly large the mountains are, or how the seas carry both power and calm. Language fails there.

But take someone to Alaska, and let them stand there, breathe it in, feel the scale of it – and they are changed. Let them witness it for themselves. Let them record their own testimony, not in words borrowed from someone else, but in something lived.

That’s what astrophotography is for me. I didn’t just capture it – I spent the time bringing it into focus, into color, into clarity. In doing so, I met the work of our Creator halfway, and in that meeting, I was changed.”

That’s my answer in a nutshell; yours might be different, but it’s worth finding.

Consider this: virtually every astrophotographer eventually takes a picture of the Moon, and of crowd-pleaser objects like the Orion Nebula or the Andromeda Galaxy. These are iconic targets: the “Eiffel Towers” and “Grand Canyons” of the night sky. You might wonder, doesn’t the world have enough images of the Moon and Andromeda by now? Do we really need another one? The answer is yes, absolutely, because each of us needs our own experience of them. Just as millions of people have taken photos of a sunset, yet your photo of that one special sunset on your vacation is unique to you, taking your own shot of the Andromeda Galaxy is a personal milestone. It’s one thing to see a gorgeous Hubble image of a galaxy in a book or online. It’s another thing entirely to spend a night capturing your own photons from that galaxy and seeing it appear on your screen, knowing you did it yourself.

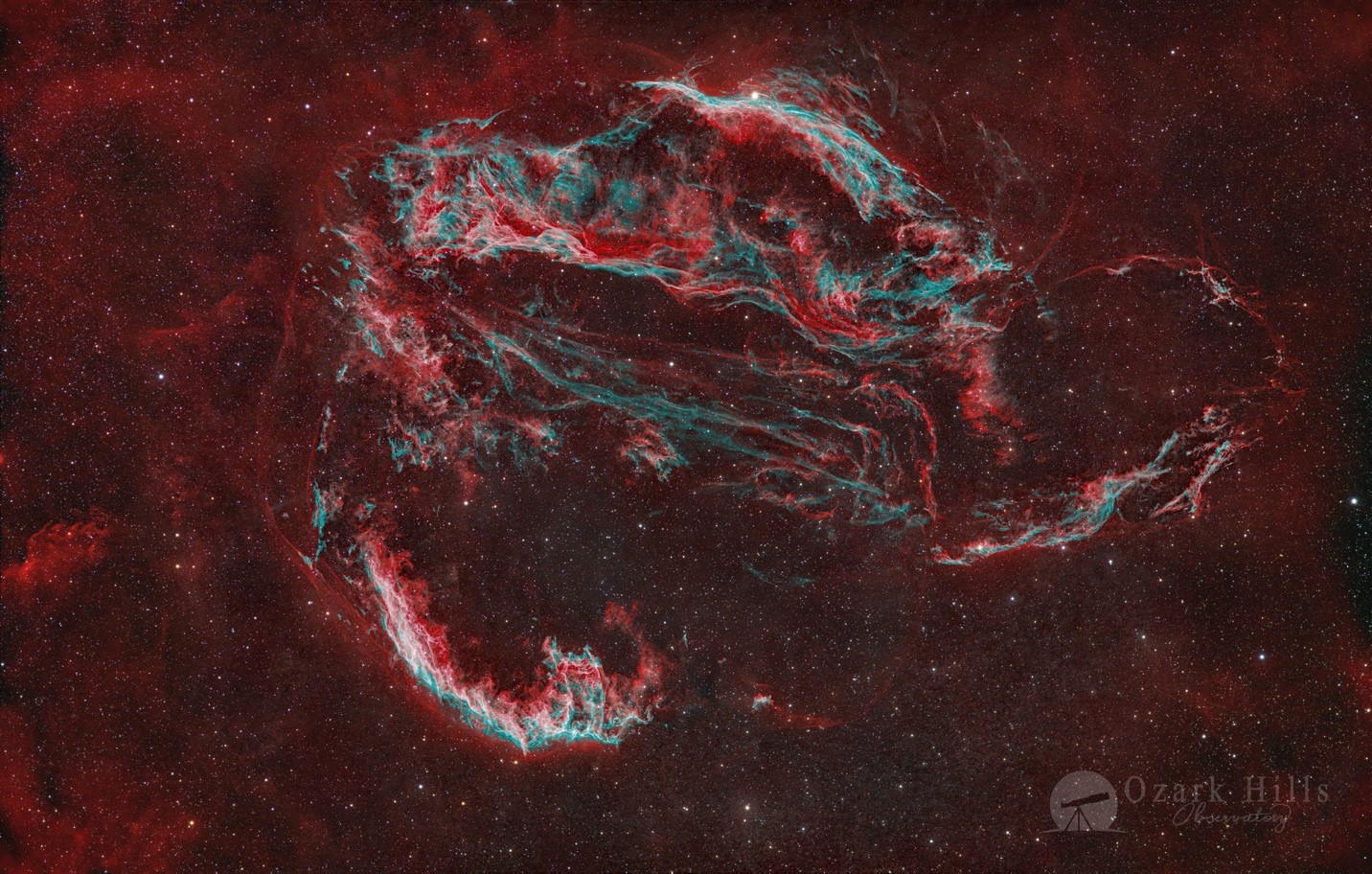

It’s like the difference between seeing travel photos of some famous mountain versus actually going there to hike it – as I said about Alaska above. We climb the same mountain many have climbed before, not to discover a new peak, but to discover something in ourselves through the journey. In the same way, when I photograph a well-known nebula that thousands of others have imaged, I’m not expecting to unveil a brand-new celestial object (okay maybe a little). But I’m doing it to experience that nebula firsthand, to create my own version of it, and to feel that connection as its starlight meets my camera. Every person who points a lens skyward has their own eyes, their own perspective, their own life context. So each astrophoto, even of a familiar subject, is a self-portrait of the photographer as much as a portrait of the sky. It reflects what the sky meant to them at that moment in time.

There is a moment that many of us seek, whether consciously or not, in the midst of our astrophotography adventures. It’s that moment of awe when you truly confront how vast and mysterious the universe is. Sometimes it happens when you stare up at the Milky Way on a moonless night and suddenly feel dizzy thinking about the billions of stars overhead. Sometimes it’s when your long exposure finally reveals the delicate spiral arms of a distant galaxy on your laptop screen. Your mind can barely comprehend what your eyes are telling it, because for an instant you grasp how enormous and ancient that object is, how still and frozen it seems, and how small you are by comparison.

That feeling is hard to put into words, but I’ll try. It reminds me of scenes from movies where a character stands before something so immense and beyond ordinary experience that they’re left breathless. Think of Ellie Arroway (played by Jodie Foster) in the film Contact, when she is transported through space and witnesses a celestial light show of galaxies and nebulae. Overwhelmed by beauty and scale, she whispers through tears that “they should have sent a poet” to describe it. Or consider the astronauts in Interstellar, struck silent as they approach a gargantuan wormhole near Saturn. It appears as a shimmering sphere of warped starlight, like something straight out of a dream. In moments like those, whether on screen or in real life under the stars, we encounter the sublime: that mix of awe, wonder, and even a touch of fear at the greatness of it all.

Astrophotography invites this feeling regularly. Each time I set up my telescope and camera, I’m essentially stepping up to face the infinite. There is a sense of adventure and vulnerability in it. You stand alone in the dark, a tiny creature on a tiny planet, daring to commune with galaxies and nebulae. It can feel a bit like standing in front of a giant dragon in a myth, heart pounding at the power before you, but instead of slaying anything, you’re simply asking to steal a little glimpse of its grandeur. Those photons that hit your sensor are like the dragon’s scales, tiny pieces of something unimaginably large. And when you finally gather enough of them to form an image, it’s as if you’ve made contact, shaking hands with the universe and saying, “I see you.”

No wonder so many of us describe the experience as spiritual. You don’t have to follow any religion to feel it. The spiritual aspect can simply be the profound sense of connection and meaning that arises when you face the cosmos. For some, like me, it aligns with faith. For others, it’s a deeply moving secular experience, a kind of cosmic oneness or an insight into the grand design of nature. The late astronomer Carl Sagan famously said we are all made of “star stuff.” Some point to the iron in our blood or the calcium in our bones as evidence that the same elements forged in stars are present within us. I believe the reveals something about the consistency of the universe.

When I photograph the heavens, I am not documenting my origin. I am recording my encounter with something I truly cannot fully comprehend. I spend hours bringing an object into focus, into color, into resolution – meeting the universe halfway in reverent attention. And in doing so, I am changed.

This image is not just a picture. It is a testimony. A witness. A quiet way of saying back to the one who made it all: I see You.

Pointing our cameras at the sky night after night doesn’t just teach us about stars and galaxies; it teaches us about ourselves. Astrophotography is a demanding pursuit, and through its demands it becomes a mirror for personal growth. One obvious lesson is patience. Unlike casual happy-snaps taken during the day, astrophotos require time and perseverance. You might spend eight hours capturing a single target, which might distill down to one perfectly crafted image. And if clouds roll in or something glitches, you learn to adapt, wait, and try again another night. This hobby will quickly train you to accept that some things are beyond your control (like the weather or the behavior of faint nebulae), and that good results often come to those who wait.

Another lesson is humility. Nothing puts life’s worries in perspective quite like spending an evening with the cosmos. The everyday stresses like an annoying email or a traffic jam tend to fade when you’re under a sky full of stars. You can’t help but feel small in the best possible way. Our egos shrink a bit when we realize the universe is vast and ancient and we’re just a tiny part of it. Yet, paradoxically, that realization can be comforting rather than depressing. It reminds us that we’re part of a grander story. Many astrophotographers (and visual stargazers, too) describe a calming, almost meditative state when they’re out in the dark, focused on the sky. In those quiet hours, you might find your mind drifting to big questions or quietly sorting out personal ones. The cosmos has a way of uncluttering the mind and bringing clarity.

Astrophotography also nurtures our curiosity and drive to improve. There’s a continuous learning curve: astronomy, physics, optics, image processing, you name it. We become eternal students of both science and art. The first time you manage to photograph something like the rings of Saturn or the subtle colors of a nebula, it’s a revelation. It’s proof that you can do something that initially seemed out of reach. That builds confidence and a hunger to go further. Okay, I photographed Saturn. Now, can I capture Jupiter’s cloud bands? Maybe I should try a really faint galaxy next. This process of challenging oneself fosters resilience and creativity. You learn problem-solving by troubleshooting guiding errors or weird camera artifacts at 2 AM. You learn to balance precision with intuition. Aligning a telescope mount to the polar axis is technical, but deciding how to frame a nebula in your image is an art. In blending these skills, you might discover new talents or a new sense of discipline in yourself that carries over into other areas of life.

Astrophotography, in the end, deepens our sense of place in the universe. It does so literally and figuratively. Literally, each photo we capture helps map our place in space. A shot of the Milky Way reminds us that we live inside a giant spiral galaxy; an image of the Andromeda Galaxy reveals our nearest galactic neighbor. Every target teaches us something about the cosmos: star clusters sketch out the structure of our galaxy, nebulae show where stars are born and die, and planets highlight the diversity of our own solar system.

Figuratively, the sense of place comes from the reflection that goes hand-in-hand with the hobby. When we connect to the cosmos, we simultaneously connect to ourselves and to all of humanity. The light from a distant star doesn’t just hit your camera; it also touches your soul a bit, reminding you that you are part of this vast cosmos and yet here you are, an observer capable of understanding and appreciating it. You feel both tiny and significant: tiny because you realize Earth is just a pale blue dot in a vast sea, and significant because you, a human being, can capture that pale blue dot or a distant galaxy and find meaning in it.

There’s a famous photograph known as “Earthrise,” taken by Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders, showing Earth rising above the Moon’s horizon. It’s often said that in going to the Moon, we discovered Earth. Seeing our world from that perspective, hanging in the blackness of space, awakened a global consciousness about our shared home. In a much more personal way, astrophotography gives each of us a taste of that overview effect. When you process an image of a galaxy millions of light years away and bring out its spiral arms, you can’t help but think, “Wow, this is out there, and I’m part of this universe too.” You begin to feel a sense of kinship with the cosmos. The stars stop being just tiny lights above; they become neighbors, ancestors, destinations, or even friends in a way (queue the soapbox and light pollution speech here).

Doing this kind of photography connects you to a lineage of sky-watchers and dreamers throughout history. You start with Draper photographing the Moon in 1840, and here you are, carrying the torch in your own backyard or remote location. You become part of the story of human curiosity. Long after we are gone, perhaps someone will look at one of our images or read our notes, the way we look at Draper’s daguerreotype or Galileo’s sketches, and feel that same spark of connection. We’re all in this grand cosmic adventure together, each generation adding its chapter.

Astrophotography may seem like it’s just about cameras and telescopes and pictures of stars, but as I’ve explored, it’s really about connection. It connects us to the cosmos by bringing the universe into our hands (a galaxy on a screen, a nebula printed on our wall), making something unfathomably large into something we can study and admire. And in doing so, it connects us to ourselves. It peels back the layers of our everyday concerns and taps into our fundamental human emotions: wonder, curiosity, humility, and hope.

When I look at a finished astrophoto that I’ve taken, I see more than just an astronomical object. I see a conversation between a human and the universe. I see a moment where I reached out for something sublime and it reached back. That picture of the Moon or that cluster of stars is also a self-portrait of my efforts, my late-night musings, and my desire to be part of something greater. It’s profoundly personal and yet universal, all at once.

So, why do we point our cameras at the sky? Perhaps because, in doing so, we are both finding our place in the cosmos and finding the cosmos within ourselves. Each shutter click under a starry sky is a humble affirmation: we are here, we bear witness to the grand beauty beyond our world, and through that act of witnessing, we come to better know our own souls. In astrophotography, the cosmos and the self reflect each other like two mirrors catching the starlight. And that, to me, is a pretty good reason to keep going out there, night after night, and capturing the stars.

#Astrophotography Tips,#Deep Sky Photography,#Backyard Astronomy Gear,#Why We Photograph Space,#Emotional Side Of Astronomy,#Spiritual Astronomy Journey,#Night Sky Photography Tips,#How To Photograph Stars,#Best Telescope For Astrophotography,#Astrophotography For Beginners,#Meaning Behind Space Photos,#Why Stargazing Matters,#Capture The Cosmos,#Astrophotography Motivation,#Connect With The Universe

– Q3 ASIWEEK Winner Gianni Lacroce’s Astrophotography Journey Hi, I’m Gianni Lacroce, an Italian astrophotographer. My passion for the night sky began long before I owned a telescope or a

INTRODUCTION My name is Marzena Rogozińska. I live in Bytom (Poland) and work as a psychologist and pedagogue at two schools. I would like to thank you for honoring my

Two years after winning #44/2023, Robert Eder, a sound engineer from Vienna, Austria, has once again claimed victory with #27/2025 ASIWEEK, returning to share his astrophotography journey. Combining technical skill

—— “Even though astrophotography is often considered a ‘solitary’passion, it is in fact very social when others help you through the toughest moments.” Hello, my name is Paweł Radomski, I

“I can say that it all started from there.” Giacomo’s connection with astronomy began early. “I’ve always been passionate about the sky since I was a child,” he recalls. At