A Retirement Spent Under the Stars: Bogdan Vuk’s Astrophotography Journey

“Astrophotography is a connection with nature, a look into space, into things we can’t see with the naked eye. It’s nice to sit in the evening under the sky next

In 1994, I built my first fully functional reflecting telescope in Hungary with my own hands. In the former Eastern Bloc countries, telescopes still could not be purchased in stores at that time—everyone constructed their own instruments, often with the help of skilled craftsmen. The optics were ground by experts at the Urania Public Observatory in Budapest for the country’s amateur astronomers.

With this 125/1000 Newtonian telescope and a homemade, motorless equatorial mount, I captured my very first images of the Moon on ISO 100 black-and-white negative film. I had to wait a full week for the results, as the local photo shop needed that much time to develop them.

My first color photo of the Orion Nebula was taken in 1997, using a hand-guided, single-motor homemade equatorial mount. The exposure time was 40 minutes on Kodak Ektar 1000 film. Around this time came the spectacular comet of the century’s end, C/1995 O1 Hale–Bopp, which I also photographed.

After that, for a long period I focused on visual observations only, taking part in school outreach programs across Hungary and leading astronomy workshops in nature camps.

The first wave of digital photography reached me in 2006 (with a Canon EOS 300D), but I did not have the time to immerse myself in it—only a few modest attempts fit into my limited spare time.

The true breakthrough for me came in 2018 with the appearance of ZWO cameras, and especially the AsiAir. Since then, I have been in continuous development.

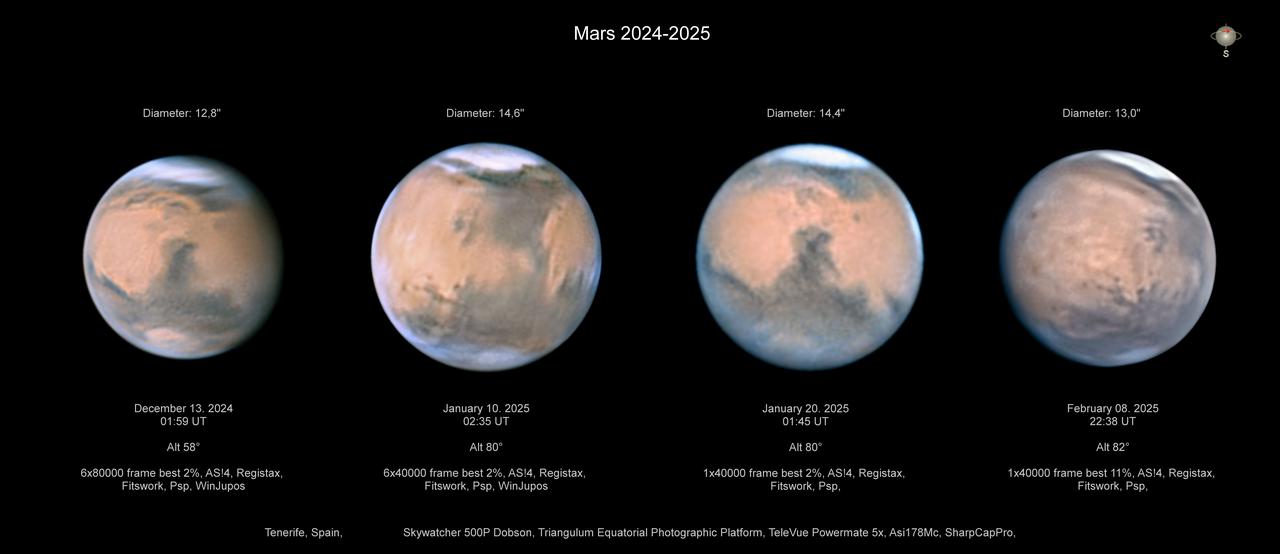

At present, my primary imaging instrument is a SkyWatcher 500P GoTo Dobsonian telescope, which has been my main setup since 2018. Although an alt-az mount is not ideal for astrophotography due to field rotation and other limitations, I am persistent. Together with my friends, I developed a dual-motor equatorial platform with ST4 guiding capability. Once mounted on this platform, the large Dobsonian became a true imaging tool.

I use an AsiAir Pro computer, a focus motor, and several ZWO color cameras: the Asi294MC Pro, Asi178MC, and Asi585MC. I greatly admire the AsiAir—it is an exceptionally well-designed and brilliant device; in fact, I was among its earliest preorder customers in 2018.

For guiding, I use a 50/185 finder scope paired with an Asi120MM Mini.

In Hungary, I photographed under Bortle 4–5 skies at an elevation of 185 meters, in the outskirts of a town of 60,000 residents. Our home’s terrace faced south, but the streetlights—especially after recent upgrades—made imaging increasingly difficult. In winter, rising smoke and warm air from neighbors’ chimneys further limited my opportunities.

In the summer of 2023, my wife Anna and I moved to Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Here we operate a stargazing business for tourists at elevations above 2,000 meters. After our programs conclude, I usually remain on site to photograph; the skies here are Bortle 1–2.

It is a breathtaking experience to stand alone on the slopes of the volcano in Teide National Park under a sparkling sky, while a few dozen kilometers away, along the coast, millions of people enjoy their holidays. At 2,100 meters, in perfect calm, the target drifts into the screen, and the imaging begins. That moment tells me everything is working flawlessly, and the next few hours will be my connection with the Universe.

I watch each subframe as it arrives, the details of galaxies, the faint streaks of distant asteroids, or the trails of meteors—sometimes visible only as a fleeting flash in the corner of my eye.

Recently, Anna has begun joining me during these sessions, and I owe this to the Seestar S30! This remarkable little instrument captivated her so much that since we bought it, she has become an astrophotographer herself.

This summer I began photographing two famous planetary nebulae: the Ring Nebula (M57) and the Dumbbell Nebula (M27). The M57 project is still not complete—I will only be able to finish it next year. I can capture high-resolution raw frames only in entirely windless conditions, and this year provided few such nights.

My image of M27, however, came together over a single calm night, and I would not have been able to process it to this standard without the PixInsight software, which is still quite new to me. The greatest challenge I currently face is the absence of Alt-Az guiding. Since I am unable to capture guided subframes, the maximum exposure time is dictated entirely by the accuracy of the GoTo system. In general, I can take unguided images of about 3–5 seconds each. Occasionally, exposures of up to 10 seconds are possible, though this depends heavily on precise alignment and the target’s position in the sky.

The Dobsonian mount does not track as accurately near the zenith as it does closer to the celestial equator. Due to the lack of guiding, the image drifts slightly over time, which I must correct manually with fine adjustments every 20–30 subframes.

My photograph of the galaxy NGC 1055 was selected as the winner of Week 43 in the ZWO ASIWEEK competition.

Several of my images have been awarded “Astrophotograph of the Month” on the online platform of National Geographic Hungary:

I aim to achieve the maximum resolution possible with my 508 mm optics. I am currently experimenting with a rotator to eliminate field rotation, and I have already succeeded in removing the diffraction spikes around stars using 3D-printed masks. My goal is to acquire a full-frame ZWO camera with smaller pixels and to develop a guiding solution for alt-az mounts.

Professional-level astrophotography has become accessible to me through ZWO devices. Now that my wife has joined me, we spend our time together under the stars as well.

“Astrophotography is a connection with nature, a look into space, into things we can’t see with the naked eye. It’s nice to sit in the evening under the sky next

Houston, Texas, USAShooting deep-sky targets from a Bortle 9 zone? Most would say it’s nearly impossible — but not Clint Shimer. Living next to a brightly lit baseball field in

In our third feature with longtime ZWO friend Michael Tzukran, we take a deeper dive into his astrophotography journey, technological evolution, and unforgettable nights under the desert sky. Although many

This time, we spoke with astrophotography enthusiast Cody Bancroft, who shared his personal experience of trial, error, and eventually finding clarity through the right gear. When Cody first started astrophotography,

Astrophotographer Callum Wingrove is based in the suburbs of London under Bortle 7 skies, where he primarily images from home using focal lengths between 135mm and 860mm. Earlier this year,